eBay Marketplaces: 3 apps (Core, Fashion, Motors)

Facebook: 5 apps (Core, Messenger, Whatsapp, Instagram, Paper)

LinkedIn: 3 apps (Core, Contacts, Recruiter, and until a few days ago, CardMunch)

Google: 36 apps (ridiculous)

Across mobile, the companies most serious about mobile are disaggregating their features sets and building new, more focused, apps. There are compelling reasons to split up your apps:

- Apps get one chance to get key permissions from the user — push and geo, in particular. With multiple apps, you can ask multiple times, and users might have a clearer understanding of why the permissions are necessary. And if one of a company’s apps annoys users, the users are less likely to totally cut out that company (by revoking permissions in all apps).

- Smartphone screens are small — even on the largest Android devices. Focused apps can have simpler user interfaces, without hidden features. If a button isn’t visible, most users will never find it. This is why Facebook removed their slide out navigation panel and why Venmo’s right nav surprised me. RedLaser has a left navigation, but we find that users are orders of magnitude less likely to use any features there.

- Updates take time on iOS. If you’re testing new features which might anger customers or be unstable, it’s better to test in less important apps and eventually roll the best and most stable features into the core experience.

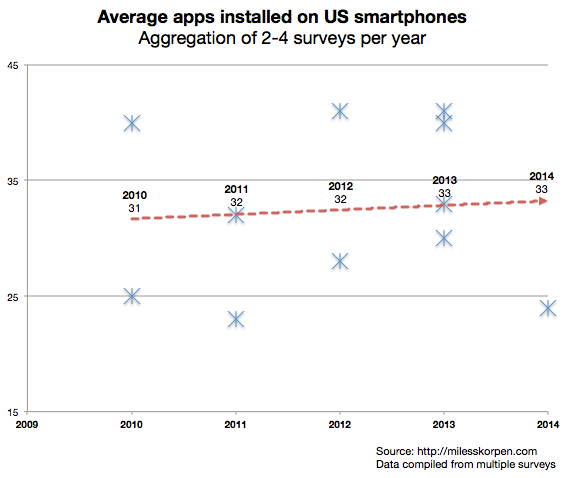

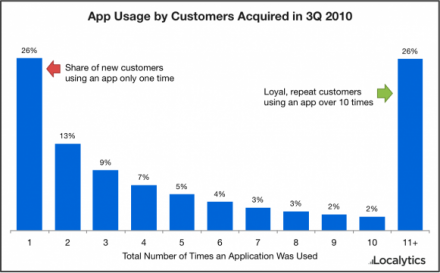

However, most users don’t have many apps on their devices: Surveys suggest users have only gone from 31 to 33 apps on their devices over the past five years. (See my data here.) Moreover, most of these apps are likely games.

If users don’t have more apps, who is using these more focused apps? A few hypotheses:

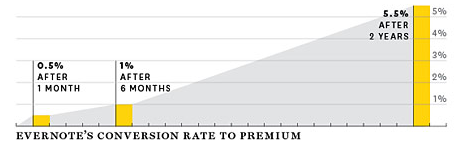

- Power-users use anything other than the core apps (and maybe Whatsapp). App manufacturers can create power tools for some users without distracting most of their user base.

- Apps from powerhouse developers are beating out smaller companies. eBay/Facebook/Google/etc. have a larger share of the install base than they did 4-5 years ago.

- None of the ancillary apps have significant install bases. They’re purely used for experimentation, and all the successful features will be rolled into the core apps.

- The cohort of users with smartphones in 2010 might have many more apps installed in 2014 — but the average is weighted down by new late-adopting smartphone users.

I suspect all these explanations hold a bit of truth. It’ll be an interesting place to watch — particularly because discoverability of installed apps becomes a huge issue once users have 100+ apps. I’m already at the point where any apps off my home screen are accessed via Apple’s built in search feature or Siri.